Tuesday, 1 November 2016

Great Gilbert Scott!

A number of years ago, when wandering along the Euston Road in London, I came across the then abandoned Victorian Gothic extravagance of the former Midland Grand Hotel, which fronted on to the St Pancras railway station. The original hotel, with its red brick spires and sweeping curved driveway up to the station, was designed by George Gilbert Scott and opened between 1873 and 1876. It ceased to be a hotel in 1935 and was used as railway offices until the 1980s, when it was shut down.

Today, it is hard to imagine a time when such a massive structure in such a prominent location could have been, effectively, abandoned, but this is what happened to the Midland Grand Hotel. In common with the nearby Kings Cross Station (which I have written about previously), the area appears to have been simply left to fall apart, and it was commonly known, when I was young, as almost a no-go area, famous more for prostitution and drugs than for its architecture, or as a desirable location in its own right.

When I walked past the building fifteen or so years ago, it was a sorry sight. Its windows were grimy and its original entrance was fenced off. Litter and dust collected on the wire fence and in its steps, whisked along by the wind-tunnel that is the Euston Road, and it was far from inviting. I was surprised, therefore, to see that a gate in the fence by the entrance was open, with a small sign inviting visitors to enter and explore. Always a fan of abandoned buildings, I looked around me, because despite the sign inviting me to do so, it still felt a little illicit, and walked in. I seem to remember a bored security guard sitting inside the front door, but other than that I was free to explore some of the ground floor rooms.

The building felt sad and unloved, with peeling paint, strip neon lighting, and damage caused by water leaks. One room, which I have since learned was originally the Coffee Lounge, had been stripped what I imagined to have been 1960s-era suspended ceiling, installed when it was an office. This had left a "tide mark" on the walls under the ceiling tiles, which had been painted more recently, and the old hotel walls above, which were of a different colour. Above it all was the original ceiling, still with grand moulded plasterwork, but punctured all over by holes from the installation of the suspended ceiling.

One of the most famous elements of the Midland Grand Hotel, even in its dilapidation, was the Grand Staircase. A striking feature of cast iron, with red and gold walls, it had been used in numerous films (such as Ian McKellan's Richard III) and music videos and, probably thanks to set dressing, was still recognisably that of a luxury hotel (even if it also had a hint of steampunk, with its mesh of industrial ironwork and faux Gothic stone).

I revisited the hotel again recently, as I was early for another appointment. It has been extensively refurbished and developed since I last visited, and it reopened in 2011 as the 5 star St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel London. The old entrance lobby (the new lobby is up the ramp, in what used to be the taxi rank) has been turned into a bar, from whose gloriously Victorian painted ceiling hang bells. As I walked back in, it was pleasant to feel life in the old building again, although I found the bar a little cramped, without feeling cosy. I usually like to sit in hotel bars and write, but I did not feel particularly inclined to do so here.

I walked past the Coffee Lounge, which is now the Gilbert Scott dining room, and registered how mightily it had been improved. Nevertheless, I felt a little sorry that this room, with its curved walls and windows looking out on the city, was not more of a public space, as I imagine it might have been originally, but at least it is being used. The Grand Staircase is as gloriously crazy as it was, but now with a deep pile carpet. Since the lobby has been moved, there feels like less of a logical connection between it and the rest of the hotel, as it was originally designed, and I did not feel inclined to sit here either, but perhaps the experience is different for those who stay and use the rest of the hotel's amenities.

I left the hotel feeling pleased that it had been salvaged from its state of ignominious abandonment, but slightly disappointed not to have felt more welcome, although perhaps that is partly a fault of the original design (in its first incarnation, after all, it only survived as a hotel for about 60 years). The architectural style is not to everybody's taste, which is one of the reasons it was been abandoned for so long, but thanks to creative thinking and massive investment, it now has another life, one that it playing its part in revitalising the wider area.

Wednesday, 14 September 2016

Long way up

Recently, having returned to the Lakes to try and tick off some more of the Wainwrights, I had a full hand of the above irritations. I had slept badly, and as I trudged to the start of my walk, the valley was overcast, with the cloud sitting discouragingly low on the hills I was proposing to climb. Nevertheless, it had stopped raining, and I started my walk, determined to at least give it a go, before the weather and my own dozy sluggishness defeated me. Very soon, it turned from wet to warm, and I had to remove my rainproof jacket. Even then, it felt like walking in the tropics, and my glasses refused to stay on the bridge of my nose, but repeatedly slid down on a slick of sweat that poured off my reddening face.

Slowly but surely, I reached the top of Seathwaite Fell (a hill of around 600 metres in height). There, sitting by Sprinkling Tarn, I ate some lunch, and drank a small bottle of orange juice with indecent haste to try and quench my parch. Across the little body of water, I could make out the lower slopes of Great End; at 910 metres, the highest hill I was aiming for. I say "lower slopes", but I suppose I really mean "cliffs", and it was far from clear where the route I had picked out on a map actually led. Having fed, I headed towards the cliff wall, and scanned it again for a way up. Eventually, I made out The Band, a kind of breach in the hill's ramparts, which was supposed to lead to another path that would eventually climb up the hill.

I am not a walker who disdains the SatNav, and today I found mine particularly useful in confirming where on the bleak side of this hill I actually was. SatNav can only lead you so far, however, and I was fortunate, eventually, to pick out the subtlest hints of a pathway leading up the apparently otherwise unassailable rock. To the experienced walker, the polish on well-worn rocks and the occasional line of grit amongst the native rocks are all indicators that you have not lost you way, and I was relieved to follow them. Then they abruptly stopped at a twenty foot high wall. I looked up at it. There might, it occurred to me, if one was feeling adventurous, be just the barest hint of steps, but I was walking alone, and was wary about getting myself rock-bound; that terrifying sensation of being unable to go forward or back, without the risk of a fall and a breakage.

I retraced my route a little and scanned the rocks around me. No, I had followed the right route; this was it. I returned to face the mini-cliff and reevaluated the scariness. On reflection, it seemed slightly less terrifying, and before I knew it, I had scrambled up it, and onto the next stage of the climb. I am not normally a walker who enjoys scrambling, but as the climb progressed, I found myself enjoying the mental as well as the physical exertion. One of the greatest things about walking is its capacity for clearing the mind of everything but the essential. One cannot worry about deadlines and other work problems, when you are also at least partly focused on not dying, for the moment.

Eventually, the gradient lessened, and I finally took a moment to turn around and see where I was. For the last half hour or so, I had been climbing in the mist, so I was not expecting to see very much. It was with a tangible surge of emotion, then, that almost as I turned, the cloud lifted, and I found that I had an exceptionally glorious view all the way down to Derwent Water, about six miles away. I breathed deep of the clean mountain air, and grinned. This, I muttered to myself; this is why I do this.

Monday, 12 September 2016

I'm not afraid of any ghosts

God, but I love New York. Even before I visited it, I think that I had been building up to loving it, having been quietly indoctrinated by watching countless movie and television representations throughout my whole life. Nevertheless, I was dumbfounded by how much - and how hard - I fell for the city. Even now, over a year after my first visit, I feel an enormous sense of almost proprietary pride in the place, and a passionate longing to return to it, whenever I see something about it.

Perhaps, films aside, it has something to do with the truly international nature of the city, almost more than any other I have visited. An example of this was driven home to me, whilst wandering the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, almost obscenely overstuffed with art from all over the world. My attention was drawn, in particular, to a bust of Caroline Campbell, Lady Ailesbury, created by her daughter, Anne Seymour Daimer, Britain's first famous woman sculptor. The sign beneath it noted that a copy existed in a church in England, and my girlfriend asked me if I knew it. I replied that, yes, I knew it. My parents had been married there, and it was where I had been Christened.

For all the high culture, it is also hard when walking around the city, not to be distracted by the many many famous film locations one comes across. In the year that has seen a new Ghostbusters (brilliant, go see it), I was reminded of finding the iconic firehouse (more correctly known as Firehouse, Hook & Ladder Company 8) at 14 North Moore Street at its intersection with Varick Street in Tribeca. Like the film tragic that I am, I sought out the location and, later, 55 Central Park West (below), another key location from the original Ghostbusters was the line between real New York and film New York blurred that little bit more.

Saturday, 10 September 2016

Pinewood, wouldn't you?

I have just achieved something that I feel like I have been waiting a lifetime to do; visited Pinewood Studios, near Iver Heath to the west of London. I went to see the recording of a comedy for the BBC, but for me the real reason for going was to be allowed inside the studio gates and have a bit of a look around. Sadly, Pinewood Studios do not do tours, nor do they allow casual visitors; they provide facilities for visiting production companies, and are naturally protective of their clients' confidentiality and intellectual property. For that reason, there are plenty of signs prohibiting photography, and studio audiences are not permitted to wander at will around the streets.

I didn't care. Just being there was enough. I have been wanting to visit Pinewood since I was a child. An avid fan of James Bond from my early years, I was well aware that Pinewood was the spiritual home of the series, and as I grew older, I was delighted to discover that the S.P.E.C.T.R.E. training base in From Russia With Love was actually Heatherden Hall, the Victorian manor house in whose grounds Pinewood Studios developed. The car chase in Goldfinger, in which Sean Connery's Bond crashes his Aston Martin DB5 into a wall, was also filmed in the back alleys of Pinewood Studios; today, the location of his crash is named, appropriately enough, Goldfinger Avenue.

I arrived ludicrously early for the recording, something that was not lost on the friendly security guard whom I asked for directions, and after abandoning my car in the Visitor's car park, I went for a wander around the perimeter of the studio. Turning left out of the grand new entrance gate, pictured above, I walked north along Pinewood Road, and was pleased with my view of the latest incarnation of the famous Albert R. Broccoli 007 stage, one of the largest sound stages in the world. It was originally built in 1976 for The Spy Who Loved Me, to house an enormous Ken Adam set, and has been destroyed by fire twice; in 1984 and 2006, the current version being completed in 2007.

Off to the right, new sound stages are springing up, the Studios having finally been given the green light to expand. As I walked along the road, I could just make out tantalising glimpses of sets wrapped up in black plastic on the new backlot, but the extension has been developed with large earth bunds protecting the view from nosy gawkers, like me, and I could see very little.

Just before the road bent round to the left, I noticed a small wooden gateway, which I realised excitedly followed the western boundary of the original studios, and I went in. This turned out to be part of Black Park Nature Reserve which, owing to its location, has also featured in a number of films, including Goldfinger, where it doubled for Switzerland in the night time car chase. It has also been used to film the 2006 version of Casino Royale, as well as Batman, Sleepy Hollow, some of the Harry Potter films and Robin Hood.

From the delightful woodland path, I could see marquees bering signs reading "Crowd Make Up". Further on, tall red-brick sound stages loomed, away off to my left and, eventually, the enormous blue-screen that backs onto the large exterior water tank came into view, through the trees. Cutting through a path to Pinewood Road, I walked back up the road to the gate, past the original mock-Tudor studio entrance, which now appears to be a turning for the local bus. New houses have been built, across the road from the old gateway, in what has been named, perhaps inevitably, "Bond Close".

Later, after the recording, we were directed back to the car park, past the 007 Stage itself. The pleasant but no-nonsense stewards were keeping us on the walkways marked on the roadways, but it was tantalisingly close. After a brief internal struggle, after which I decided that I would kick myself if I did not at least try to make the most of this chance, I approached the nearest steward and asked if I could leave the path and touch the stage. She considered the question and, to her credit, did not openly mock me for asking. Eventually, she agreed, provided I did not take any photos. Thanking her, I sprinted across Broccoli Road and slapped my palm against the concrete of the 007 Stage; I had touched the Bond Stage. It was all I needed, and it made me very happy.

Labels:

007,

Albert R. Broccoli,

Aston Martin,

cinema,

DB5,

film,

filming,

From Russia With Love,

Goldfinger,

Iver Heath,

James Bond,

Pinewood,

Pinewood Studios,

Sean Connery,

set,

sound stage,

Studios,

The Spy Who Loved Me

Tuesday, 2 August 2016

Ealing nostaligic

I have a minor addiction to film studios. I think that it might have begun when I was taken around Universal Studios in Hollywood, as a child, although having said that, by then I had already had bursts of obsession about Charlie Chaplin and the early days of Hollywood, so I may already have got the bug.

I'm not sure what it is that I find so fascinating; perhaps it is the sense of anticipation at what might come out of them. Possibly, it is the amazing skills of the artists who build sets, create special effects, or perform in these modern cathedral-sized spaces, or maybe even it's the last ember of a childlike fantasy that I might, if they did but know it, have something to offer the film makers inside. Whatever it is, if I am near a film studio, I cannot resist the urge to go and have a look (usually at not very much, given tight security).

Nowadays, however, I do occasionally find myself wandering around the backlots of Pinewood and Shepperton, thanks to the magic of Google Streetview. As regular readers will know, I also thoroughly enjoyed visiting the Warner Bros. Studio Tour, even if I am one of those pedantic people who knows and is still slightly bothered by the fact that the sets that you walk around are not actually in the real studios where the Harry Potter movies were filmed. Instead, just to spoil the magic slightly (although, to be fair to the Tour, they do not pretend otherwise), they are in a specially built venue next door. The "real" Leavesden Studios, where the films were actually made, is tantalisingly over the fence next to the car park.

So it was with gentle satisfaction, then, that I found myself outside Ealing Studios in West London, recently, the origin of some of my favourite old films, and one that is still, pleasingly, a site for the production of movies. The old entrance, above, is symbolic of the pocket-sized studios; on the face of it grand but, behind the white paster facade, very much make do and mend.

Ealing Studios are synonymous with a roughly six year run of glorious British films, which include such classics as Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), Passport to Pimlico (1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953), and The Ladykillers (1955), although they have actually been making films on the site, in one form or another, for 114 years. I grew up watching the famous "Ealing Comedies", and others of around the same era, having been introduced to them by my late father, who was as much of a film enthusiast in his day, as I am now.

I wandered along a public alleyway, between the studios and a BT building, and I was pleased to see that the small backlot, such as it is, was filled with movie trailers. I steered guiltily clear of the security guard in his box, but sneaked a few surreptitious photos. Peering over walls and fences, I took in the pile of old props and, at the back of the studios, the rickety-looking 1930s buildings, and could imagine being transported back to the time when British cinema great such as Alec Guinness, Joan Greenwood, Peter Sellers, Dennis Price, and Alastair Sim would have been regular performers there.

Nowadays, far from being tied to its past, alongside its historic sound stages, Ealing Studios is also home to the cutting edge of cinema, in the form of Andy Serkis' studio and production company, The Imaginarium. The Imaginarium specialises in motion capture technology for film, television and video games (including for the most recent Star Wars film). Peering nosily into one of the windows on the first floor of the old entrance, I realised with a start that I must actually have been looking into Mr Serkis' office; a carved wooden gorilla perched on the windowsill being one of the clues (Andy Serkis performed, via motion capture, the title role in 2005's King Kong). Maybe, one day, I'll get to have a proper look around some studios, but for now I'm happy to indulge my addiction from afar.

Thursday, 21 July 2016

Hidden glory

There are times when small moments of wonder surpass more demonstrative spectacle. An example of just such a moment is to be found in the tiny church of All Saints' in Tudely in Kent. From outside, it is not particularly different from many other churches in Britain, with its squat brick tower and porch. Inside, however, it is hard not to be moved by the thing that makes it stand out from the rest, indeed from any other church in the world, and that is its stained glass windows, all of which were created by Marc Chagall.

The Chagall windows began in 1967 with the east window, pictured above, which was commissioned by Sir Henry and Lady d'Avigdor-Goldsmid as a memorial to their daughter, Sarah, who had died in a sailing accident in 1963, at the age of 21. This background is reflected in both the colour and the imagery of the window, above which is a horse, which some have identified as symbolic of freedom or love. Although the reason for the window's creation is tragic, the colour of the window and the way in which the eye is drawn upwards, creates a strongly uplifting feeling, in keeping with many of Chagall's other works.

It is said that Chagall was reluctant to accept the task of creating the memorial window, but that when he visited for its installation, he said of the little church, 'It's magnificent. I will do them all.' The rest of the church's windows were installed in 1985, the year of Chagall's death, and now the church is open to everybody to marvel at them. Apart from the rarity of an entire church with windows by such a prominent artist, and their undeniable beauty, the fact that they remain in the space for which they were designed, with all of the meaning that goes with that, renders them truly magical.

At Tudely, because the church is so small, the majority of the windows are at eye level and one can stand close to them. This means that it is possible to become completely immersed in them, to be bathed in their colours, and to see the hand of the artist. When transplanted into the sometimes antiseptic environment of an art gallery, some otherwise great art can lose its spark, and it is easy to forget the context for which they were created. Here, the work still feels powerful and relevant, and it is a joy to behold.

Labels:

art,

Chagall,

church,

England,

Marc Chagall,

stained glass,

Tudely,

UK,

window,

windows

Tuesday, 5 July 2016

The Life Aquatic

As the lazy afternoon drifted by, we came at last to the almost deserted beach, and I could feel my heart lift. The pebble shore curved away round the little bay, lapped by gentle waves, and the jade green sea rippled seductively in front of us. It had been many years, several decades indeed, since I had been to Corfu, and I had been concerned that it would not be possible to find a beach that was not bordered and disfigured by the garish and noisy trappings of tourism. And yet, here was one that felt as it if might have come straight out of Gerald Durrell's My Family and Other Animals, a book that has long been one of my favourites.

This beach was bounded by a little-used road, with only a couple of quiet tavernas set along it at a discrete distance from each other, both of which seemed to exist in a drowsy parallel universe, from a time long gone by. As I walked slowly into the crystal clear water, gently acclimatising myself to what felt like the cold, but which probably only felt that way in contrast with the warmth of the day, I glanced down into it. Already I could see the darting flashes of small fish, and I sighed through my snorkel in contentment, as I let myself slip into the sea.

Finally submerged, I floated for a while, entranced by the underwater soap operas being performed before me. I thrilled at the neon vividness of the ornate wrasse, as it shot between the larger pebbles, and I floated after small schools of annular sea bream, their almost translucent iridescent bodies flexing beneath where I hung in the sea above them. After a while, my submerged ears became accustomed to the clicking of the little sea bream, and I watched as they snapped at each other and other passing fish (including me). On one occasion, two little fish performed a strange ballet, swooping away from each other, before turning, dashing back, and locking mouths, with an audible snap, a performance they repeated again and again. I could not tell if they were flirting or fighting but, after watching them for a while, I thought that I should give them some privacy, and I drifted on.

A small red ragworm floated free of its tiny pebble cave, where I had seen it crawl a little earlier, and I held myself back as it was attacked by the little fish around me. It twisted and turned, as if suspended in mid-air, its centipede-like feet flailing, before it finally made its way back to the sea bed. There, presumably feeling immensely relieved after its ordeal, it wriggled itself between stones for safety and did not reemerge. A tiger-striped comber, not much bigger than my index finger, saw me, turned and swam back to the shade of an overhanging pebble, and its disguise blended it perfectly into its sanctuary. Another little fish, with brown frills like a flamenco dancer, looked up at me, and we stared at each other for a while. Slowly, it opened its tiny mouth, either in amazement, or as if it thought that it was a much larger creature, and might attack me. To spare it the embarrassment, should it attempt the feat and fail, I turned politely and swam away.

As the sun arced around the bay, and disappeared behind towering grey thunder clouds, it felt like the time had come to move on for the day. I emerged from the sea, feeling that familiar sea-salt tingle on my skin, which brought back memories of my childhood, learning to swim in the sea off the coast of Devon. Driving back along the coastal road, we spotted a sign pointing to the Durrell White House, and I turned off to see it. The house is more overlooked by other houses than it was when Lawrence and Nancy Durrell made it their home in the 1930s, but sitting on the rocks beside the terrace, it was not hard to imagine how it might have felt when they were there. Across the little bay of Kalami, and away beyond the headland dotted with olive and cypress trees, a fork of lightning split the sky, followed some time later by a far off rumble of thunder. It was time to go.

Wednesday, 29 June 2016

Vikos Gorgeous

In the Pindus Mountains in northern Greece lies the Vikos Gorge, a geological record-breaker, which is claimed to be the deepest gorge in the world (being 900 m, or 2,950 ft deep and only 1.1 m or 3.6 feet between its rims). Visiting in June, we were driven along the twisty mountain roads from our hotel in Aristi, to the north, to Monodendri in the south by our charming host, whose English was limited, but whose generosity and kindliness was not.

We had been advised to start early, at 6 am, but were delayed by breakfast and a wrong turn on our way down into the gorge, and did not begin until nearer 7.30 am. We had started by walking most of the way to the monastery of Agia Paraskevi, built on the edge of the Vikos Gorge, before being called back by our host, who had tottered after us in wooden wedges, which were distinctly unsuitable for the ridged pathway. We had just reached the gateway to the monastery, and decided that there was no safe way down into the gorge from there, when we saw her following us along the path, calling us to return, and made our way back to the village, and from there down a different street.

Finally on the right course, walking down the winding path to the bottom of the gorge, we relished the cool breeze that occasionally wafted through the tree-dappled sunlight. It had been a hot couple of days; the heat so intense that, stopping for lunch in the town of Ioannia the day before, I had heard the pine cones crack in the sun, the reports sounding like gunshots.

Reaching the bottom of the gorge, we walked along the dry riverbed, occasionally exploring its water-scoured rocks, as the sun rose beyond the towering mountainous sides beside us. At one point, I stopped, arrested by a strange animal noise off to the left - a repeated half bark, half howl - which even now I cannot confidently identify. The gorge is home to bears, wolves and boar, among other animals, and as we walked quickly away from the sound, as much as I tried to be reassuring about it being behind us and no threat, I could not help keeping an eye on the path for decent-sized throwable stones, in case of an emergency.

Further on, and comfortably removed from whatever has made the noise, I was delighted to find a pool in the rocks beside the dry river, in which I saw first tadpoles, and then several frogs of increasing sizes. Flow in the river is seasonal, and underground watercourses mean that one may hear water running, but only occasionally see it on the surface. This little pool was a perfect pond for this group of amphibians, the water level of which was presumably refreshed from time to time by rainfall.

The walk from Monodendri to Vikos, to the north of the gorge, is supposed to take between four and a half and six hours, but by the time we neared the final stretch, and the climb back out of the gorge, it was past midday and the the blazing sun had well and truly risen, which slowed our progress considerably. The shaded wooded pathway gradually petered out, and the way ahead of us became dry and exposed to the heat, with only the occasional patches of shade, between which we dashed as quickly as tired legs and the extreme temperature would allow.

Despite having hiked and climbed in equatorial Africa, this felt like the hottest walking I had ever done. Although I was happy that I was protected against the sun, I began for the first time to worry about heat stroke. As the sweat ran off me, I could not avoid the thought that this had become a dangerous situation, with which my body was not coping very well. Noël Coward's line "Mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun" repeated in my thumping head, and I could feel my heart pounding fiercely and too fast.

By pouring half the contents of our drinking water over ourselves, we managed to keep on just the right side of exhaustion and we forced ourselves on, desperate to get out of the heat. As we eventually climbed out, over the lip of the gorge at Vikos, I gave thanks to whoever had built a stone shade with a water tap, which stood across the road. I put my head under the cooling water, and felt both relieved and revived as my pulse and breathing returned to a more normal rate. 'Next time,' I said, gratefully letting the water run down my sweat-drenched shirt, 'We start at six.'

Labels:

Aristi,

climbing,

Gorge,

Greece,

heat,

Ioannia,

Monodendri,

Noël Coward,

Pinsu,

Vikos,

walk,

walking

Monday, 13 June 2016

Mooning around Stockholm

In Gamla stan, the Old Town of Stockholm, there sits a statue of a boy looking at the moon. The figure is called Järnpojke, or Iron Boy, and was created in 1954 by Liss Eriksson. He takes a bit of finding, partly because he is tucked behind the Finnish Church, near the Stockholm Palace, and partly because the boy is only 15 centimetres (5.9 in) high (making him the smallest public monument of Stockholm).

With a little time to kill, and having heard about the statue, we wandered around Gamla stan, occasionally stopping to peer around the occasional church, in search of the right one. Eventually, we gave in and looked up it location online, because otherwise we could have been searching for hours. Seeing the figure, however, repays the effort. The boy may be small, and his features indistinct, but he is undoubtedly charming, and there can be no question but that he is looking at the moon.

When we arrived, we discovered (as is, apparently, the custom) that somebody had provided him with a small woollen hat (which I removed, only temporarily, for the picture, above, but then returned with care). In the winter, apparently, he is also given a small scarf to keep him warm against the Swedish cold, which appealed to me enormously, as I like the idea of a community collectively agreeing that what is, objectively, a lump of cast iron is, in fact, a person to be cared for.

Waiting for the Ghost Train

Tucked away behind undergrowth and wire fences, near the A66, beside Bassenthwaite Lake (the only "Lake" in the Lake District, tedious pub trivia fans; all of the other lakes are actually "Meres" or "Waters") stands the crumbling remains of what was once Bassenthwaite Lake railway station. The station was part of the Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith Railway but, along with the rest of the line west of Keswick, closed on 18 April 1966, just over a century after it was opened.

I have always found something rather fascinating about exploring old ruins; as a child, I braved the wildly overgrown ruin of a large house at the end of my village, and for a long time afterwards was obsessed with the vacant rooms I had found, with tantalising hints of their former grandeur. Even today, I love the strangely surreal atmosphere of coming across buildings slowly being reclaimed by nature. So it was, having finished a short hill walk in the Lakes earlier in the year, that I realised I would be passing the ruins of the old railway buildings on my way to my hotel.

Some time before, whilst distracted at work one day and exploring Google Streetview, I had seen the ghostly outline of the old station building beside the main road. There has (and remains) some talk of reopening the line between Penrith and Keswick, which greatly appealed to me, although I fear that it may remain a unrealised dream of enthusiasts. Wist reading about it, I had been looking into the old railway that served this part of the Lakes. Later, I read The Lake District Murder by John Bude, in which the main characters frequently travel up and down this line, investigating shady goings-on, and was curious about this one of many abandoned railway lines. Since its closure, the Keswick to Cockermouth stretch of the railway has been built over, as the A66, which means that, with a little effort, one can imagine a little of the old journey.

I parked the car up a side road and approached the remains of the station building. It roof having been removed (or collapsed), it was clearly in a bad state and it was fenced off, with signs warning against trespass. Not wishing to do so (and, anyway, being unable to find a practical way through the fences), I walked around to the front of the station, along what I realised would have been the track-bed in front of the platform. The elegant wooden waiting room, also without its roof, was still recognisable, with its red and cream panels fading and overcome by mildew, and I could make out the ticket window in what I presume was the station master's office beside it.

Walking along the platform, whose edging stones remained beneath a carpet of moss, it did not take a great deal of imagination to see the building in its heyday, although somehow this made its current state all the more forlorn and sad. For a functional building, it had been created with very pleasing elegance, as I suppose was the way things were done in the 1860s. I wondered whether the craftsmen who laid the stone and created the woodwork ever considered that there might come a time when their hard work would be left to fall apart, but then reflected that few of us think of the future like that. It had been a smart building on a railway line, and presumably something that its station master and railway staff had devoted time and care to maintain, but its time had passed.

Returning to my hotel along the A66, I passed several other obviously railway-related buildings, which had now become homes, and was pleased to think that something of the old railway, beside the course of its old line, remained and was in regular use.

Labels:

Bassenthwaite,

Cockermouth,

England,

Keswick,

Lake District,

Lakes,

Penrith,

railway,

ruin,

station,

UK,

United Kingdom,

walking

Thursday, 26 May 2016

Five star gossip

I had forgotten, because I had not done it for quite a while, just how entertaining it is to sit in the lounge area of a five star hotel and to listen to the various conversations going on around you. Today, overlooking the Thames, I'm in the middle of three different American business conversations, each of which conform to different cliches of that type. To my right, a grouchy gentleman is complaining, either to the people sitting around him, or to somebody on his hand-free phone - it is hard to tell which - about a business deal of some sort, the details of which he appears angrily not to understand.

To my left, more excitingly, another American gentleman is telling numerous stories of his dealings with the Russians, a group of people he likes, but apparently treats with caution. "In the broker business..." he continues, in what, looking back over it, appears to be an almost uninterrupted monologue directed at his younger female companion, whose level of interest in his yarns it is hard to judge. I gather that his dealings with the Russians date back to the very end of the Cold War, and he confirms my suspicions, when he talks about having been advised that some of his dealings might lead to a knock at the door by men in dark coats.

I'm sitting here to take advantage of the comfortable seats, the complimentary wi-fi and the coffee which, whilst it might be fractionally more expensive than that in Starbucks, comes with all of the above, and an almost unbeatable view out over the Thames. From time to time, the riverboats pass in front of me, which suggests that it must be high tide. It feels very different, in here, from the hot day outside, and I savour my coffee and velvet sofa, on which I am making myself very much at home.

I remember when this hotel, the Mondrian London at Sea Containers, was a beautifully appointed, yet somewhat unapproachable set of offices. When it was built, it had been planned as a hotel, but the financial situation in the seventies meant that started its life as offices and had to wait over thirty years before being open to the public as originally intended. It remains, to me, one of the most New York-like hotels in London, with its "Dandelyan" bar beside the river serving a range of cocktails. Its restaurant also serves one of the best breakfasts in London, although it is worth aiming for brunch time, and allowing for enough refills from the buffet to see you through most of the rest of the day.

Labels:

bar,

cocktail,

cocktails,

coffee,

Cold War,

five star,

gossip,

hotel,

London,

Mondrian,

New York,

River Thames,

Sea Containers,

Thames,

United Kingdom

Monday, 16 May 2016

Lion around

Sometimes, cities and towns want to stop cars driving along certain roads. They can do this in several ways, such as by erecting fences, bollards, signs and barriers, but in Stockholm, Sweden, a decision appears to have been taken that the best way to do this is to use beautiful, smiley, concrete lions. From what I can tell, they are almost purely functional, but the fact that they have been endowed with such pleasing countenances, entirely fits with my impression of the Swedes as having a tendency towards almost casual beauty, when it comes to design.

You notice it even on the motorway from the airport to the City, where bridges and fly-overs are artfully lit or architecturally elegant, and a little extra care seems to have been taken to make something fundamentally necessary into something that is pleasing, too. Even a massive advertising sign is crafted so that, from behind, it resembles the stylised silhouette of a tree.

Quite why more places do not seem to follow this principle, I don't know. Clearly, some civil engineering adornments come with significant added cost, and one could be forgiven for arguing that they may not be essential. The problem is that we have to live with these things - bridges, and barriers and streetlights and advertising hoardings - and making them the most basic versions of the things they have to be is not always the most pleasing.

I think that we should be careful not always to opt for the purely functional. That is not to say that the purely decorative is necessarily the only desirable outcome (although, naturally, great art is uplifting, too). I suppose what I am saying is that, where we need to have, for example, a street light, the outcome could be achieved with, essentially, a lightbulb on a stick. That should not, however, mean that that is all we get. Some effort should be expended, and we should encourage that it is expended, to make the mundane and the functionally necessary beautiful as well. This is something the Swedes and the Danish appear to believe, and it is an attitude that other could learn from.

Friday, 29 April 2016

You rang, Mallard?

I paid a flying visit to Edinburgh recently, to see some friends and the band Frightened Rabbit, although by the time I returned home, I felt partly like I had been on a tour in tribute to Sir Nigel Gresley. Sir Nigel is possibly most famous for being the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the London and North Eastern Railway, and for the steam engines he designed.

Those of you who have read this blog before, something that strikes me as unlikely but remotely possible, will already be aware from my post Steam Work, that he was the designer of Mallard, the fastest steam engine in the world (which reached 126 mph (203 km/h) on 3 July 1938). Among other achievements, he had also designed the famous Flying Scotsman, which had only recently been renovated and undertaken a celebratory journey from Kings Cross to York. This train, as many will also be aware, was equally famous, being the first steam locomotive to have reached 100 miles per hour (160.9 km/h), which it did on 30 November 1934

When I arrived at Kings Cross, which I still find impressive for its successful meshing of modern and old, I discovered that only a few days before, a statue had been unveiled to Sir Nigel Gresley. I did not know it at the time, but there was a campaign running to reinstate a companion statue of a mallard duck, which had originally been planned to accompany Sir Nigel, to commemorate not only the engine of the same name, but his apparent fondness for feeding ducks at his home. I recalled Sir Nigel, from my trip to the National Rail Museum, and took a picture of the statue, thinking no more about it.

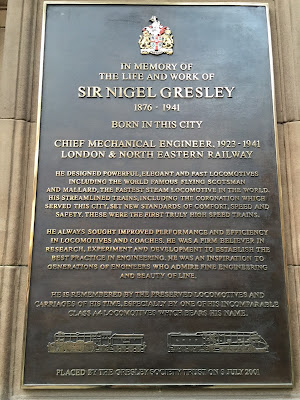

The next day, whilst admiring the fine waiting room at Edinburgh Waverley railway station, pictured above, I discovered a plaque commemorating the life and work of Sir Nigel, who had been born in Edinburgh 140 years before...

and on the train heading back down south, I noticed a large sign beside the track, commemorating the spot, at Stoke Summit on the East Coast Main Line, where in 1938 Mallard had set the world speed record for a steam locomotive. It was gone in a flash, but it felt like a sign, in every sense of the word. We can never know what impact we will leave on the world, but at that moment, it felt that Sir Nigel had definitely made his mark.

Tuesday, 19 April 2016

Bring me sunshine

On the seafront in Morecambe, Lancashire, caught midway through his famous dance, stands a glorious statue to one of the town's most famous sons, Eric Morecambe. Born John Eric Bartholomew (as recognised in the name of a pub in town), the genius of Eric Morecambe needs no explanation for British readers, although he may be less well known further afield. A comedian, best known for his double act with Ernie Wise, Morecambe was a well-loved television personality, and was a particularly great star in the sixties and seventies (Morecambe and Wise's 1977 Christmas show on the BBC is reputed to have had an audience of around 28,385,000).

I had known about the statute in Morecambe's home town for some time, and had always wanted to go and see it but, despite passing reasonably close to it many times, on my way to the Lake District (which you can see in the background of the photograph, above), I had never gone out of my way to pay it a visit. Morecambe, the town, has a bit of a reputation for, to be generous, its faded glory, so I was pleasantly surprised, when I did finally make the effort to go to find it had a pleasant promenade along the seafront, and an air of quiet business. A typical English seaside town, its days of being a thriving tourist destination are very clearly past, but there was nevertheless a sense of minor optimism about it, of an effort having been made to attract the visitor, and it was nowhere near as dispiriting as I had imagined.

The statue of Eric Morecambe had, a little time before, been removed after a vandal had apparently tried cut it off at the leg, but it had been restored, and was just as joyous - even more so, in fact - as I had anticipated. For a man who brought a great deal of joy to many millions of people, it was heartwarming to see the genuine affection in people's faces, as they politely waited their turn to have their photographs taken with his statue. Most, like me, posed for their pictures with one leg in the air, their arms waving, in tribute to the statute's subject, and all of them, from what I could tell, were smiling; many, myself included, were properly grinning.

It says something about the warmth with which Eric Morecambe is remembered that even a statute of him (brilliantly rendered by sculptor Graham Ibbeson, including binoculars in honour of Morecambe's fondness for birdwatching) brightens up people's days. Even the thought of it, and its effect on those who had come to see it, cheers me again.

Wednesday, 13 April 2016

Feeling sheepish

The Lake District has a number of famous inhabitants. Depending on who you ask, they might mention Dorothy and William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the other Lake Poets, Beatrix Potter, Arthur Ransome or Alfred Wainwright, author of the famous Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells. For other people, some of the most famous residents are there still, and will carry on doing so for many years; not the humans who call Lakeland their home, but the Herdwick sheep, 99% of whom are estimated to live in commercial flocks in the central and western dales of the Lake District.

Herdwicks are especially robust animals, and live solely on forage, but tend not to stray, which makes them especially suited to the hills of the Lake District. For those of us who do not farm, the Herdwick sheep are also very distinctive, with their brown wooly bodies and faces seemingly with a perpetual amicable smile, and many people, me included, find them endearingly charming. This pleasing visage is perhaps what prompted the Herdy Company in England to produce a range of Herdwick-inspired products which, with their stylised Herdwick face peeping out, can be found in shops all over the Lake District.

Seeing the Herdwick sheep, perhaps as much as the familiar outlines of the Lakeland Fells, is one of the ways that makes me feel that I have arrived in the Lakes; little brown clouds pottering across the slopes and fields beneath the peaks. It's at least partly because of that pleasing symbiosis that I have a Herdy mug on my desk, when I'm not out walking the Lakeland fells.

Labels:

Arthur Ransome,

Beatrix Potter,

Coleridge,

England,

farming,

Herdies,

Herdwick,

Herdy,

Lake District,

Lake Poets,

Lakeland,

Lakes,

sheep,

UK,

United Kingdom,

Wainwright,

William Wordsworth

Saturday, 19 March 2016

All the world's a Globe

The London I used to know from my youthful ramblings, twenty - goodness me, is it really twenty? - years ago is, slowly but surely, giving way to a polished, sandblasted, homogenised version of its former self. For example the old Globe Inn in Borough Market (which, to be honest, I never went in twenty years ago, because it looked far too scary) has literally been sandblasted to a bright London-brick yellow, which looks both clean and yet also pretend, like a film set's painted plaster wall, masquerading as the real thing.

This is a little ironic, I suppose, as I recall coming across the filming of the first Bridget Jones film, which was being made here in 2000, and discovering that a completely fake set of railway stairs had been inserted under the arches beside the pub (in the flat above which is where Bridget Jones lived, in the film). Even then, the fake stairs had art-department painted bird droppings and graffiti to make it look authentic. At the same time I am reluctant to be unduly critical of the motivation to reclaim or repurpose otherwise near no-go areas for general use.

This area, for example, used to be grotty, smell of rotting food waste from the market, and be best walked through at a reasonably swift pace after dark. It's just that the edges have been knocked off, smoothed over, and sanitised. It seems improbable that the "characters" of old - Jeffrey Bernard, Peter O'Toole and the like - would thrive in this cleaner, gentrified, non-smoking version of London, but then perhaps their time was an anomaly - a symptom of their own post-WWII era.

I get the sense that there's a tussle going on, between the forces of regeneration and the original residents and users of the space. During the week, between 2 a.m. to 8 a.m., Borough Market is still, as its name suggests, a real wholesale market, selling fruit and vegetables, as it has done since at least 1276 (or maybe since 1014, according to the market itself, "and probably much earlier").

From Wednesday to Saturday, however, it also becomes home to stallholders, selling a wide range of food and drink from across the country and abroad (inevitably, there are a lot of "artisan" products and producers), and it is a destination in its own right for foodies and visitors after interesting tastes. Quite what the early morning vendors make of the later tenants, I don't know, but it would be interesting to see the handover between the two.

Saturday, 12 March 2016

Kenya dig it?

A couple of years ago, along with about a dozen other supporters, I visited Kajuki, a small village in Kenya, to see the work of a small UK charity called St Peter's Lifeline (to which I would urge you to donate. Visit: www.stpeterslifeline.org.uk). The charity supports the work of St Peter's primary school and community through education, micro finance, empowering girls, feeding programmes, clean water, sanitation and the prevention of disease. The community was extremely poor, with repeated periods of drought hitting its agricultural economy hard, but the people we met were, almost without exception, hard working, positive and optimistic.

We spent several days travelling around the area, seeing the work of the schools, anti-FGM campaigners and micro-finance groups, all of which was immensely impressive and deeply moving. At the end of a week, we were waved off by the community in the same way that we had been greeted, with a typically dazzling display of warmth and hospitality, and a farewell performance of singing and dancing. It had been intense but wonderful and we left the community bearing gifts and very powerful memories. It had been arranged long in advance that, after seeing the work of the charity, and contributing to it by our visit, we would spend another few days on safari, seeing the wildlife of Kenya.

We arrived at Sweetwaters Serena Camp on the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, a massive safari park and wildlife preserve, after a long and dusty drive along the Meru-Nairobi Highway. The camp itself was essentially an open-air hotel with large tents instead of rooms, arranged around an old colonial farm building. The drive itself was fascinating, with the dry and dusty roads around Kajuki gradually giving way to lush verdant meadows, north of Mount Kenya. Watching as it slipped past, I was reminded strangely of driving through Somerset in England, although on a somewhat grander scale. Further on, there were the vast greenhouses beside the road that provide other countries with cut flowers and out of season vegetables, and we mulled over the pros and cons of a poor country that can struggle to feed its people using precious water and resources to grow food for others.

The Camp felt like an alien world; geographically close to the people we had spent time with, but it was an international and luxurious hotel that felt a million miles away. Around us were holiday-makers from all over the world, for whom this would, by and large, be their only experience of the country, and as we regrouped at breakfast and dinner, eating well cooked international cuisine, I could see that most of my group were equally dazed by the contrast with where we had just come from. Its very easy to sound po-faced about insensitive tourists, and I wouldn't want to pretend to have been much more than that myself, but it was hard not to feel that it was unjust, such abundance so close to people who had become friends, and who, in contrast, had so little.

We were here to see the animals, though, and as we were driven out into the Conservancy, it was hard not to get caught up in the search for wildlife. The first drive was a little underwhelming, only seeing an elephant at some distance, and then a herd of zebra. Later, when we went out again, we saw giraffes, and then, trundling slowly down a dusty side track, came almost literally face to face with the glorious lioness shown above. We were standing up in the safari truck, and she felt close enough to touch. There's something intangibly thrilling about making eye contact with such a powerful wild animal, and after taking a few pictures, I just watched her as she watched us. I found myself narrowing my eyes at her, an instinctive greeting towards cats, and felt, just for a moment, that we understood each other.

Wednesday, 2 March 2016

Hogwarts Express yourself

The interweb is a wonderful thing. This may sound like a trite observation, and that's predominantly because it is; it's a fantastically trite observation, but that doesn't, I'm pleased to report, stop it being true. Of course, there are bad parts of the internet, areas that upset, offend, humiliate and degrade, but then there are other areas that go at least some way towards making up for the rest.

I only bring this up because it has come to my attention that a recent post about a visit to the National Railway Museum in York was astonishingly - almost bafflingly - popular with you good folk out there in the interwebsphere. Particularly, for some reason, readers in Poland. Witam moi polscy przyjaciele! Anyway, it occurred to me that it might be interesting to test whether it was steam trains in particular that appealed, or something else and, while about it, I thought I'd throw some Harry Potter into the mix, too. Cynical, you say? Well, yes, possibly, but what is a body to do?

Anyway, the current reason that I have decided the interweb is, at times, a wonderful thing is the fact that, without it, I doubt I would have found out so much about Hogwarts Castle, the steam train on display at the Warner Bros. Studios, Leavesden (otherwise, and possibly more widely, known as the "Harry Potter Studio Tour"). I visited the Studios last year, and was absolutely bowled over by the entire experience; the scale and detail of the sets, salvaged from the film series, the quality of the invention, and he craftsmanship and imagination on display.

Even for people who are not interested in the Harry Potter films, per se, the experience is nevertheless absolutely overwhelming. I have long held a slightly obsessive interest in film studios (did you know, for example, that Google Streetview lets you take a walk around Pinewood and Shepperton Studios? You should check it out.) and the Warner Bros. Studios more than lived up to my potentially unrealistic expectations.

Leaving one section of the tour, visitors enter into a recreation of King's Cross, complete with an honest to goodness, large as life, real steam engine, Hogwarts Castle. This engine is the actual one from the films (unlike the recreations on display at the theme parks), emits smoke and the sound of a steam whistle, and is as physically imposing as some of the engines in the National Railway Museum. Although Hogwarts Castle is a real steam engine, however, as befits that fact that this is an artificial film world, neither the steam nor the sounds that come from it are the real thing, but are special effect recreations to evoke the appropriate atmosphere.

What I have recently learned from the interweb, and which started this post oh so long ago, is that Hogwarts Castle, as perhaps befits a feature player in a film, is not the engine's real name. In real life, Hogwarts Castle is the GWR 4900 Class 5972 Olton Hall, and I gather that steam enthusiasts regard the fact that a "Hall" plays the part of a "Castle" to be wryly amusing. Oh, the interweb, you do spoil us, sometimes.

Labels:

engine,

Great Britain,

Harry Potter,

Hogwarts,

Hogwarts Express,

King's Cross,

Leavsden,

National Railway Museum,

Pinewood,

Poland,

Polish,

railway,

railways,

Shepperton,

Steam,

U.K.,

UK,

Warner Bros

Sunday, 21 February 2016

Who nose?

There is almost always something unusual to see in London, if you are on foot, are reasonably observant, and are in the right mood. Sometimes, the things worth seeing are large and obvious, like a film shoot (which always makes me childishly excited) or a statue; other times, the things are small, like an unobtrusive sign pointing towards a "Roman Bath" (as may be seen on Surrey Street), or a brass plaque set into a wall or pavement. Regular readers may already have an idea that I enjoy spotting blue (and other coloured) plaques, commemorating the home or workplace of famous people from history.

On Admiralty Arch, between The Mall and Trafalgar Square, is a particularly small object of interest, and it's one that is often overlooked by passers by. Attached to a wall on the northernmost arch is the nose you can see above. It looks as if it is made of bronze, but I understand that it is made of plaster of Paris and polymer, and it is attached to the wall about eight feet from the ground. I cannot recall how or when I first became aware of it; I might have read something somewhere and gone looking for it, or I might have just spotted it, as a slightly incongruous protuberance on a large public building and landmark.

However I came to find it, I like that it is there. Apparently, it was placed there in 1997, along with around 34 others in various locations around the city, by artist Rick Buckley (www.rickbuckley.net) as part of a campaign against the "Big Brother" society. According to an Evening Standard article in 2011, approximately ten of Buckley's noses remain, including in front of Quo Vadis, a restaurant and private club in Soho, and somewhere outside St Pancras Station.

An odd thing about the noses, which only now occurs to me, is that - possibly because they are of such a mundane object, the human nose - one may be aware of them, but then forget about them when they are out of sight. I have a vague feeling that I have seen the St Pancras Nose which, from the photos I have seen on the web, appears to be a clay red colour, to blend in with the bricks to which it is attached, but I am not absolutely certain. There's something pleasing, however, about a work of art that retains a slightly covert character; although they are not hidden, you will only find them if you seek them out, or discover them by accident, and either way, if you do come across one, I challenge you not to raise a smile.

Thursday, 18 February 2016

Steam work

The mighty steam engines that surround the enormous turntable in the Great Hall of the National Railway Museum in York can take away the breath away. Partly, it's the fact that several of the engines gathered here (and the engines on display change, from time to time) are not just the fun little steam engines from most remaining steam railways, but are the enormous giants of steam history - Mallard, the Duchess of Hamilton, the Evening Star. These steam engines are at once beautiful and physically imposing, like mighty wild animals that have - just about - been tamed.

I first visited the National Railway Museum around thirty years ago and, whilst I think I have retained a vague sense ever since of the presence of the engines, for some reason the place was not entirely familiar when I went back recently. Doubtless, this unfamiliarity may have had something to do with a change in displays, and in museums in general, over the intervening three decades, but as I walked around these shining testaments to engineering, it dawned on me that I was experiencing them from an entirely different level to last time. Aged around seven or eight, I was probably a couple of feet shorter than today, and the engines around me must have been even more vertiginous and awe inspiring than they are now.

Visiting today, one doesn't need to remember what the experience of viewing these machines was like as a child, however, because there's something immensely childlike about being allowed to be in close proximity to such vast objects. I realise that plenty of people find great joy and fulfilment in watching modern trains go by, and I am certainly not going to mock trainspotters; the fact remains, however, that, by and large, modern trains don't manage to capture the same sense of excitement, of sheer raw almost animal power, as their ancestors.

The old trains, in comparison, along with the obvious mechanics that make them go - steam pipes, pistons, cylinders, crank shafts - they can also be almost heartbreakingly beautiful; the Duchess of Hamilton (the red train in the picture, above, designed by William Stanier) is "streamlined", meaning that she hides her boiler and pipes beneath a curved red ballgown of immense elegance; Mallard (the blue train, above, designed by Sir Nigel Gresley) is a stylish and graceful curve that one can easily imagine carving a path through the night air, art deco clouds billowing in its wake.

The other thing that makes these objects so fascinating, so enigmatic and worthy of attention, is the knowledge that, when they run, they are genuinely alive, in a way that diesel and electric trains just aren't. Steam engines (in the UK, at any rate) rely on the burning of coal - and lots of it - to heat the water to make the stream that drives the pistons that turns the wheels. This belly of fire, like a dragon's, relies in turn on the hard manual work of a fireman (and it does usually appear to have been a man's job) physically shovelling coal - tons of coal - into the firebox.

Today, standing in the cab of the Mallard, it's hard to imagine how it must have felt when engine was at full speed (it still holds the world speed record for a steam engine, which it reached on 3 July 1938, of 126 mph (203 km/h)). The heat, the roar of the engine, the fire and the wind, and the smoke and dust from the coal are almost unimaginable, but time spent among these mighty beasts is the closest many of us are likely to get to what must nevertheless have been a thrill.

Saturday, 6 February 2016

Feeling a bit King's Cross

King's Cross station in London has changed a lot in recent years. For the longest time, passengers were disgorged from the underground station into a grimy, frequently rainy, forecourt under a sprawling, utilitarian, and deeply unlovely awning. Pedestrians were squeezed between a wall of dull glass-fronted kiosks and the busy Euston Road. Inside the station, passengers huddled together, in a crowded and confused space before the train tracks, hoping to catch sight of their train listing on the display boards. There were few seats to be had, and the whole experience was, on the whole, pretty dismal and depressing.

Britain's railways, dating back to their early days, contain examples of some spectacular engineering and architecture. Following the decline of (and massive underinvestment in) the railways in the 1960s, however, the nation's railways and their buildings felt for many years like a coma patient in terminal decline (pun half-intended). Stations became grimy utilitarian spaces, where they had once been glorious statements of an expanding nation's self-confidence, and it felt like there would be no reversal of the relentlessly downwards spiral.

Then something happened, in relation to Kings Cross, at any rate. Between 2005 and 2007, a £500 million restoration plan was put in place, the old mess of buildings in front of the station was done away with and, on 19 March 2012, the new - glorious - station concourse, shown above, was opened to the public. It occupies a space to the left of the old station and, with its organic-looking vaulted roof, new shops and a mezzanine floor with restaurants, it now feels as if passengers are welcome to the station rather than, as was the case before, a regrettable inconvenience.

I arrived at the station early for my train, and wandered around the new concourse, utterly entranced. It does perhaps, speak volumes for the previous standard of railway travel in Great Britain, that a decent location warrants surprise and pleasure, but be that as it may, I found myself delighted. I pottered around the large airy space, marvelling at how sensitively the new merged with the old, each enhancing the other.

The original station offices, which I cannot recall at all from the old station, have now been repurposed (or, perhaps, returned to their original, logical, purpose) as ticket offices and shops, and the original yellow London brick buildings feel, if it is not too fanciful, to have a restored sense of pride. I was pleased, but not entirely surprised, to discover that in 2013 the restoration project had been awarded a European Union Prize for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Award.

King's Cross is known to millions of Harry Potter fans across the world as the location of Platform 9 3/4, and the Harry Potter Store to one side feels appropriate, as does the luggage trolley disappearing into the brick wall. When I was there, a long queue of fans was waiting to have their photo taken, Hogwarts scarves flying, pretending to be about to join the Hogwarts Express. Elsewhere to my childish delight, a falconer was flying his hawk around the space to deter pigeons, and the station felt - as I like to imagine it might have felt when it was first built - like a vibrant and exciting place to start a journey.

Tuesday, 26 January 2016

Shelling out for the underground

Margate, on the northern coast of Kent, is an unusual place. On a sunny day, and they do occur, the beach around which it is set presents an appealing arc of sand, along which a glittering sea laps, attractively. To one side, the striking Turner Contemporary art gallery - a modern addition to the waterfront, and an attempt to trigger wider investment - draws the eye and a lot of visitors who, but for its existence, would probably have come nowhere near this otherwise somewhat dilapidated seaside town.

This is partly because, behind the gallery and seafront, lurks Old Margate. Bits of it, without question, are attractive and interesting, and blue plaques record the home of John Le Mesurier and Hattie Jacques (whose birthplace is also marked, here), and the building where Eric Morecambe and his wife held their wedding reception. Other parts of Old Margate are, regrettably, more problematic. Like many British seaside towns, with the rise in package flights to sunnier climes, Margate suffered from the decline in "traditional" seaside holidays, and its descent towards (if not downright into) borderline poverty is etched on its crumbling buildings and neglected spaces.

Walking away from the sea front, past buddleia-bedecked derelict sites awaiting money or inspiration, or both, the atmosphere, whilst not exactly threatening, is nevertheless somewhat less than welcoming. All towns and cities have their slightly unloved, but ultimately utilitarian, areas and Margate is hardly to be blamed for appearing to have more than its fair share of them. Nevertheless, the further from the sea we walked, the less sensible the plan that we had seemed to be.

Eventually, the road we were seeking came into view, and we turned left, climbing up a sloping and otherwise entirely residential-looking street. A little way up, on the right hand side, was the entrance to the building we were looking for, if "building" is quite the right word. We had arrived at the "Shell Grotto", an underground passageway, in essence, lined with shells; an exceedingly strange attraction, in an extremely unlikely location.

After paying our entrance fee, we wandered into a small back room, which contained background information on the grotto, such as it is possible to ascertain, which does not appear to be much. For example, one of the signs posed the questions, "Why was it built? When? Who by?" and answered them concisely with, "We don't know."

Descending a small stairway at the back of this room, we found ourselves in the grotto proper. A shell-lined circular underground corridor with an arched roof leads to a small atrium with a domed ceiling, through which daylight enters. Beyond this, a further passage gives access to rectangular room known somewhat sensationally as the "altar chamber", one end of which is blank cement, a testament to bomb damage from the Second World War.

As with a lot of the Grotto, definite information is sparse, so whether it was part of some religious temple, or just somebody's crazy whim is impossible to say; the grotto appears to have been discovered (or, at any rate, its existence made public) in 1835, but other than that, the rest is largely speculation, including just how old it actually is. Whatever the reason, date or individuals behind its creation, it remains an arrestingly odd place, and definitely worth a visit. Just don't go expecting to learn anything very definitive, other than perhaps what it is like to be in a shell-lined tunnel underground.

Sunday, 24 January 2016

Wainwright away

Between 1955 and 1966, Alfred Wainwright published seven volumes of a pocket-sized walkers' guidebook called "A Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells". In the course of doing so, he identified 214 hills and mountains (known as "fells") in the Lake District in Northern England which have come to be known, collectively, as "the Wainwrights". For those of us who are so inclined, myself included, it has become a common past time to walk or "bag" those fells and to "do the Wainwrights".

Not all of us, however, have ready access to the Lake District, and so the process of walking all 214 fells can take several years. Fitter and, for the slower among us, more annoying people have achieved the same thing in six or seven days, but I like to think that they could hardly have savoured the experience. Another advantage about the process being more drawn out is that each time I return to the Lakes, I experience anew the sensation of joy and happiness that comes from the effort of propelling myself over beautiful landscape, with often even more stunning views around me.

And so it was this weekend, when I returned to the hills, almost ten months after my last visit. Having started my car journey pleasingly early, I arrived in the North Lakes in good time to climb Binsey, a low Wainwright, somewhat detached from the main bulk of fells that he catalogued. As it can take me at least five hours' driving to get to the Lakes (sometimes as much as seven or eight, if the traffic is against me), I have occasionally considered some Wainwrights as "expensive", meaning that the effort required to get to and then walk them is relatively great.

If I were to have travelled here to climb Binsey on its own, and nothing more, it would have been an extremely "expensive" hill, being only 447 m (1,467 ft) high, and so removed from its neighbours that it would not have been particularly practical to combine it with any other hills. As it was, I had a longer walk planned for the next day, so this was a bonus. Being only a pleasing 50 minute climb there and back from the car, this gently walk was also exactly what I needed after my drive.

Looking back south over the Skiddaw massif and Bassenthwaite Lake (the only "lake" in the Lake District, trivia fans; the others have "mere" or "water" in their names) having reached the modest summit, I felt refreshed and renewed, almost instantly. The fresh air, the bright sunlight, the endorphins, all combined to blow away the cobwebs that can accumulate, living predominantly indoors over winter, and I found myself grinning broadly, despite myself.

The next day, I walked and walked and walked. I had been planning to climb two other Wainwrights, but as I wandered over the fells, and saw the proximity of several others, I ended up climbing five. I turned back from a possible sixth, as the wintery wind filled with razor-sharp droplets of freezing rain, which pinged harshly against my face, but I was still satisfied. Looking back, on my way off the hill, the wind and rain having abated and the sun breaking through the clouds again, I wished, for a moment, that I had pressed on, but you never know what the weather will do in the Lakes, and it could easily have got worse.

The hills will still be there another day, I considered, and it's always good to have something to come back to.

Wednesday, 20 January 2016

Hodge your bets

In Gough Square in the City of London stands the above statue to Hodge, Dr Johnson's cat (whose ears, I can't help but feel, are actually just a little too big). I first met this Hodge around Christmas time, one year, when he had a collar of tinsel, and a pleasingly festive air. He stands, on a plinth, outside Dr Johnson's house, on which is written "HODGE a very fine cat indeed belonging to SAMUEL JOHNSON", repeating a quotation attributed to him in in James Boswell's Life of Johnson. Dr Johnson is supposed to have said of his pet "He is a very fine cat, a very fine cat indeed."

There is something deeply humanising about hearing about how famous historical figures interacted with their animals, and indeed the names they gave to them. Hodge is a great name for a cat, but I think that I slightly prefer the name given by Edward Lear to his tubby tabby cat - Foss. I have also always liked the story about Hodge, again told by Boswell, that Dr Johnson would go out himself to buy oysters for his cat, rather then make is servants do it, so that they wouldn't dislike Hodge for having been put to extra work.

Labels:

Cat,

cats,

City of London,

Dr Johnson,

England,

Gough Square,

Hodge,

London,

oysters,

Samuel Johnson,

UK

Thursday, 14 January 2016

Jurassic Parklife

Sometime in 1852, sculptor and natural history artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was commissioned to create 33 "life-size" models of extinct animals (including, most famously, dinosaurs) out of concrete, to be displayed to the public. The fact that the very idea of dinosaurs was relatively new (the name "Dinosauria was only given to these creatures by Sir Richard Owen in 1842) and not altogether well-understood (Darwin's "On the Origin of Species" was not published until 1859) does not appear to have dissuaded Hawkins unduly. Over the following three years, accordingly, and in collaboration with Owen and other paleontologists, Hawkins set about creating the arrestingly odd collection of figures that are still on display in the grounds of Crystal Palace in South London today.

I had heard about these unlikely beasts years before, but only recently had determined to actually make the effort required to visit them and was still unsure what to expect. The Crystal Palace site is, itself, a remarkable remnant of times past. Although it was the second location of the enormous glass exhibition hall, first erected in Hyde Park for the Great Exhibition of 1851, just about all that remains of it is the footprint of the giant building. Below this are the surviving steps leading down to wide terraces, whose glory days of supreme manicuring are, presumably, long gone.

The building itself burned to the ground in 1936, having been moved from Hyde Park (and greatly expanded in the process) in 1854. Wandering about the ruins today, and seeing tantalising hints of what might have been, tucked away behind wire fences and beneath the undergrowth, here and there, it is hard to escape the feeling that the world that the Victorians experienced, for all that it had undoubted and extreme deprivations for many, was also almost unbelievably breathtaking; an age of supreme ambition. Even before its move and inflation, the original Crystal Palace in Hyde Park was 1,851 feet (564 m) long, 128 feet (39 m) tall and with 990,000 square feet (92,000 m2) of floor space, and in its new location its scale only increased.

Today, several levels below where the Crystal Palace once stood, despite years of ridicule for their appearance, once dinosaurs became better understood (and their 1850s appearance having been dismissed as inaccurate), having been ignored, overgrown, rediscovered and restored (more than once), the dinosaurs still reside beside their pools of water. They were most recently restored in 2002 and are now Grade I listed buildings (pleasingly, the same classification as Buckingham Palace and the Palace of Westminster). They are, without question, an odd day out. In fact, and with all due respect to them, they probably do not merit a complete day in themselves (if you're interested, it's also worth checking out the Park Farm, nearby, as well as the ruins of Crystal Palace) but they are certainly worth a visit.

They are broadly laid out in different geological eras, and include figures of prehistoric mammals, but it is the dinosaurs, including the iguanodons, pictured above, that are the real draw. Don't go expecting a real life Jurassic Park experience; these beasts are static and don't really accord with our current understanding of what dinosaurs looked like. Thinking abut it, however, we really shouldn't be too smug about what we consider to be "knowledge"; in my lifetime alone, for example, dinosaurs have gone from being widely believed to be big green scaly monsters, to brightly coloured feathered creatures,. Any assumption that our current era really "knows" anything should, within certain parameters, be treated with great suspicion.

Friday, 8 January 2016

As I was going to St. Ives...

It has come a long way from its origins, as a sleepy fishing village, but there is nevertheless a clear sense of a real community remaining beneath the seasonal tide of emmets (the Cornish name for tourists, from an old English word for ants - the logic speaks for itself). For many, the draw of St. Ives is the bright blue sea, and its warm sandy beaches. St. Ives is surrounded by bays, each of which offers something different for different people. For families who wish to sunbathe and paddle, there is the broad expanse of Porthminster Beach, with its cafes and restaurant. To the north west, there is Porthmeor Beach, which draws surfers and bodyboarders. Around the natural promontory known as The Island, between the two, there are three or four other little sandy alcoves, which slowly fill up with holiday-makers.